Arriving in the Isle of Man

A THROUGH VARIOUS PARTS OF THE BEING ALSO, OF AN BY AUTHOR OF MDCCCXXXVII. TO HIS EXCELLENCY LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR OF UPPER CANADA. I DEDICATE THIS SMALL VOLUME— INSIGNIFICANT INDEED AS A TRIBUTE OF RESPECT, BUT A SINCERE TESTIMONY OF A BROTHER'S REGARD. ATHENÆUM Club, Pall Mall, [Contents pages follow here.] THE present Continuation of the "Home Tour" embraces a period antecedent to that of the volume of last year. Of this fact, unimportant with reference to the matter contained in the pages, it is sufficient simply to acquaint the reader. While preparing for the press, I determined, for more reasons than one, to change my original plan of introducing at the end, a brief ramble in England of the current year. I have accordingly appended the "Memoirs of an Assistant-Commissary General" instead. The latter production, referring to an early date, conceived off hand, and unpremeditatedly put forth to the public, being explicit, needs little preface. Yet if it were at all necessary to delineate those causes or influences, whether springing from duty or inclination, that allured or compelled me to the somewhat erratic course described now and heretofore in the present and two former volumes, I have thereby at any rate, now in part supplied that deficiency. GEORGE HEAD. ATHENÆUM CLUB, PALL MALL, 29th June, 1837. THROUGH The Mona's Isle Steamer—Rough Music—A Ventriloquist —Douglas Head—Extreme Clearness of the Water—The Pier—Porters—Hotel Agents—Castle Mona—Mode of conveyance thither—British Hotel—The Town of Douglas.

THE sun shone bright, and music played gaily on board as the "Mona's Isle" steamer, one fine morning, bound to Douglas in the Isle of Man, weighed anchor, set steam, and made the best of her way from Liverpool out of the harbour. Whether or not it be right to use the expression the music played, as we say the wind blowed, it were at all events wrong to dignify the present three or four musicians by the name of a band, they being in fact sailors belonging to the vessel, owners of a set of extremely discordant instruments, and the leader a hard featured pock-marked man, who squared his elbows, stood bolt upright in a military posture, pointed the clarionet downwards in a direct line with his toes, and signalized himself by playing a great deal louder than all the rest together. The paddles meanwhile of the "Mona's Isle" steamer continued to beat time different from that of the melody as we proceeded down the river, till we were at the mouth of the Mersey; when, being in the open sea, the instruments were laid aside, the men betook themselves to their several occupations, and the paddles now drummed on by themselves in their own measure. In the space of an hour we were comfortably gliding across the unruffled channel, each passenger rejoicing in newly acquired freedom from the smoky confines of the city, inhaling a pure atmosphere, and above all well pleased to behold now securely arranged on the deck in decent order, all those identical packages and portmanteaus, that only a short time before he was following through narrow streets and by-ways with overheated solicitude, like a cow her devoted offspring in a butcher's cart, in the wake of the porter's barrow. Of the crew, one swept anew the clean white deck, another rubbed salient knobs of brass with a piece of shamoy leather, and a third devoted the whole of his care to restoring stray articles to their proper places. One of the performers, to the science of music added that of ventriloquism, and afforded by his skill, really rational delight to a numerous group both of quarter deck and steerage passengers, who were attracted to the forecastle by a performance which, though here presented to the public in humble guise, afforded nevertheless no mean specimen of a dramatic entertainment. Besides the mechanical process of his craft, the artist also exercised the functions of improvisatore, and with ready wit, good feeling, and tact, and a memory richly stored with the pleasantries of the ancient Punch, continued to keep the laughter of his hearers continually on the wing; so that it were pity to reflect, witnessing the present display of native talent, on the light of the needy dramatist thus hidden under a bushel, and extinguished by the vis inertia

of poverty, that weighs merit down. What reference the word ventriloquist can possibly bear to a faculty whereby the whole mystery is performed by the muscles of the throat, I am at a loss to know, whereas by the etymology, one might fairly presume that that indolent organ the belly, whose province proverbially is to do nothing but eat, were now about to assume a new privilege, break silence, and talk. At all events, no matter how the sound be generated, the artist has positively no control over its transmission, and although indistinctness of utterance may create a sort of impression of distance, yet for the rest of the deception, the hic et ubique

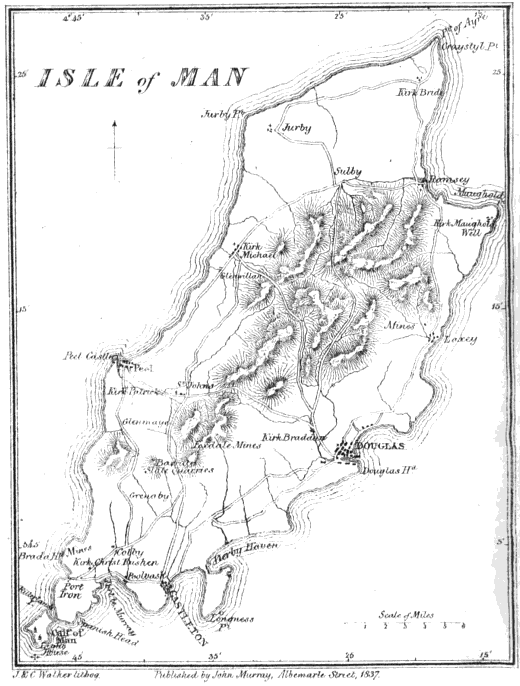

sensation of a voice proceeding down the chimney, or upwards through the window, such fantasies exist, even to their unlimited extent, solely in the imagination of the hearer. A familiar or doll is an indispensable member of a ventriloquist's establishment, and for aught we know to the contrary, the Grecian sage with his demon, was merely a ventriloquist; or at all events an autoloquist, or thinker aloud. On the present occasion, the office was performed by a small wooden effigy, in likeness of an old man with a wig, whose lips, when supposed to speak, moved extremely naturally, so as by alluring the eye to a definite point, effectually to imbue every spectator with a notion of reality. The entertainment in the way of dialogue was sustained between the ventriloquist and those of the various persons present who felt inclined to enter the list, and propose to "Tommy," for such was the doll's name, an argument or a question; to all which the latter retorted with infinite success upon his antagonists, and at the close of each sally, proclaimed by a curiously comical laugh, a consciousness of success; and having moreover the infinite advantage of never changing countenance or colour, he floored his assailants as they came to the charge, one after another. Tommy, in motley company, and of such the present group consisted, evinced propriety of sentiment, discreet phrase, and extreme good humour, and, by no means a contemptible moralist, promptly held in awe the intruder, giving people at once to understand, that though it were his vocation to keep fun for ever alive, yet he knew how to stifle at its first gasp, the breath of ribaldry. Wherefore, every female on board, feeling herself securely posted within the Rubicon of delicacy, witnessed without the slightest apprehension of offence, these amusing colloquies. A child three years old, a bold little boy, now stepped in among the rest to the foreground, and there alone commenced, without preface or fear, an earnest conversation with Tommy. By common consent all others drew back, and left a clear stage to the juvenile performer; and in the course of this dialogue, well maintained on both sides, the scene created a powerful impression; for the understanding of the child and its feelings to boot, were played upon in such a ludicrous degree, that it evidently entertained no manner of doubt that Tommy was a rational, living creature. To the new wooden acquaintance, in the artlessness of infancy, it dedicated the pure first fruits of early friendship, and with sympathies increasing more and more every moment, proposed innumerable questions relating to his history. The growing illusion at last became perfect, and after entreaties repeated in the course of the dialogue, the child finally possessed itself of the friend of his heart, and carrying away the diminutive idol, returned in a couple of minutes drowned in tears and sobs, because Tommy declined to answer any more questions. At three o'clock, the passengers partook of an excellent dinner below; after which, returning upon deck, we performed the remainder of the voyage in calm, delightful weather; the shores of England fading meanwhile fast away, and the Isle of Man in the distance rising from the sea in a straight line from end to end, although the land in the middle is so low as to create the appearance of two separate islands distinct from each other. As we neared the port, the sun, on a clear autumnal evening, sank behind the island, and as we approached the pier, we fell within the shadow of the bluff rock, called Douglas Head, whose black craggy summit, gilded by his rays, was beautifully contrasted with the peculiarly light green of the verdure on the hills, and the more than ordinary transparency of the water below. In no other part of the world, I really believe, is the sea more pellucid than on the coast of the Isle of Man, where the rivers, proportionate always in extent to the parent land, are mere brooks, and these even less charged than is usual with alluvial soil. I am quite sure it were easy at this spot, at a depth of forty feet, to count the sixty-four squares of a moderate sized chess-board. A dense cluster of the inhabitants crowded on the pier head, as is the daily custom among the town's people, to greet the arrival of the "Mona's Isle"; and we were making, as I expected, a prosperous landing, when the steam was suddenly let off, and the anchor dropped within an hundred and fifty yards of the point of disembarkation; creating thus the necessity of stepping down from the vessel bag and baggage into a boat, and landing once more from thence on the broad stone steps of the pier. It is well that measures are already in progress to remedy the evil, but, taking the pier at Douglas in its present state, there is no other I believe within the British dominions, where a large sum of money has been expended to so little purpose. Accessible, unless at the top of a tide, to no vessels larger than small fishing craft, the chief purpose to which the Douglas Pier has been hitherto applied, is that of a promenade, while the lighthouse erected at the extremity, is intercepted towards several points of the compass on the south-east by Douglas Head; on the summit of which rock, another lighthouse, elevated a considerable height above the other, and visible, as a lighthouse ought to be, from all parts of the horizon, in order to remedy the former defect, has since been built. As the pier stretches into the sea to the eastward, the south side is washed by the Douglas river, a narrow stream, mid-leg deep at its mouth at low tide; and parallel on the north side is a reef of rocks, which, as they enclose a considerably greater depth of water, it seems strange were not accordingly chosen as the site and foundation. Nevertheless, with regard to the said pier and lighthouse, whatever in future time may be the improvement, when the coast of the Isle of Man becomes resorted to for the purposes of sea bathing, at all events, even at present a gallant steamer carries the mail from England and returns every day. Not many more than fifty years ago, a lanthorn elevated on a long pole on the beach, was the only winter beacon for the poor fishermen, and a severe tempest, one dreary night, that struck with terror their little squadron, extinguished the light, and drove many boats in confusion upon the rocks, whereby the shore was strewed with those who miserably perished, and many wives next morning were there seen bewailing their husband's corpses, caused a degree of universal sympathy, that, with the aid of Parliament, set on foot the plan of the structure, and effected its completion. A traveller ascending the steps of Douglas Pier, might reasonably fancy he was about to enter the extensive precincts of a metropolis of note, such are the number of eager faces that direct their looks towards him, and such the number of obtrusive agents from the inns, of which there are six or eight at least in the town, who after the manner of "touters" belonging to stage-coaches, stand like a swarm of horse-flies in his way, each holding the respective card of the establishment obstinately under his nose. I know of no municipal regulations of more charitable purpose than such as, on occasions like these, serve to protect the sea-sick and the stranger; and such have performed wonders of late years at the port of Douglas. The above cited remnant of barbarous custom, bears slight comparison with the truly outrageous conduct permitted among the porters, at a period only four or five years ago. These fellows, now subjected to proper control, and a decent, orderly class of men, then provincially called hobblers, were of manners mitigated by no sort of discipline whatever. It was then impracticable without an effort of strength, and coming to personal issue with the offender, to prevent luggage and parcels being forcibly carried away, one knew not by whom or whither; and I have formerly seen, in the case of a person unable to take his own part, an extended line of neutral faces quietly looking on over the rails at the passing scene; namely, the owner hustled above, and half a dozen boisterous hobblers fighting for his luggage below. Notwithstanding the laudable anxiety of the agents of the several inns in the cause of the landlords, so as with equal diligence, whether the hostelry be good or bad, at all events to conduct the traveller to it; the proprietors of the Castlemona Hotel have the additional advantage of a carriage which waits upon the arrival of the steamer to enforce persuasion. This hotel was originally built for the residence of the late Duke of Athol, though some time since converted to the purposes of an inn. Its situation, a mile from the town, fronts the sea, in the centre of a fine bay, that affords an agreeable ride or drive across sands all the way from the town. A table d'hote is here provided regularly during the summer, and well attended, chiefly by residents of Whitehaven, Liverpool, and Manchester. It is curious to observe, on the arrival of the steamer, with what dispatch a full complement of passengers are acquired, and so soon as selected, how triumphantly they are driven away. As the luggage is dispatched by another conveyance, a few minutes are amply sufficient for the above operation; and as the carriage is an open one, the candidates have in fact nothing else to do but to make up their minds to go, previous to departure. The vehicle is a sort of high narrow waggon, shaped like a hearse, and so confined in dimensions, that the convenience of those who travel therein is evidently purchased at the expense of ease and grace of attitude; the passengers in fact, although probably utter strangers to each other, sitting vis-a-vis,

like onions in a string, and in a row so closely packed, that they seem pinioned, or handcuffed. In the meantime so little space is afforded between the two rows, that one man without leaning forward may readily light a cigar from the mouth of his opposite neighbour. Altogether, as I saw a dozen people crammed together in a heap, and thus whisked away from the pier-head on a party of pleasure, I could not help comparing them, owing to their ludicrous appearance, for the moment, to a set of convicts, on their way from a county gaol to the hulks, or Newgate. For my own part, during my short stay at Douglas, I found excellent entertainment at the British Hotel within the town, kept by the worthy Mrs. Dixon. At this house I was furnished with good apartments, and, with regard to fare, such was the liberality and good will of my hostess, as well as the redundancy of provisions at her command, in consequence of a four o'clock ordinary included in the ménage,

that my table was crowded with viands actually in despite of my own remonstrances, in a degree of profusion quite incompatible with the reasonable charges in the bill. Well housed and provided, with good saddle-horses to be hired, and macadamized roads to ride upon all over the island, a person not over fastidious, and desirous of a central point from whence to make rural excursions, will not in this hotel have just cause to complain either of comfortable sojourn, or the means of peregrination. There is little inducement, I think, as a permanent residence to remain in the town, for the site is low; nevertheless, although the adjacent country abounds in beautiful, picturesque spots of rural habitation, by far the greater proportion of persons, who, attracted to the island by the prospect of cheap wines and provisions, have taken up their abode therein, reside at Douglas. One very long, narrow street, forms the principal part of the old town, and contains curious specimens of the primitive, unadorned dwellings of English fishermen. The houses, mostly unequal, some large, some small, are built of rough blocks of stone; the street is passable with difficulty from its convexity, and the inconvenient manner wherewith it is pitched with irregular and acute boulders. On the elevated land, immediately contiguous and above the buildings, many new houses and villas have been recently erected, besides a handsome and spacious church below, whereof, by the way, the clerk has the sweetest tenor voice I ever heard. He was assisted by a group of young men and women under his direction, and the performance, which, without any musical accompaniment whatever, consisted of psalms adapted to ancient rural church tunes, assorted with taste and simplicity, displayed to my mind an exquisite specimen of pure English psalmody.HOME TOUR

UNITED KINGDOM.

A CONTINUATION OF THE "HOME TOUR THROUGH

THE MANUFACTURING DISTRICTS."MEMOIRS

ASSISTANT COMMISSARY-GENERAL.

SIR GEORGE HEAD,

"FOREST SCENES AND INCIDENTS IN THE WILDS OF NORTH AMERICA."LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

SIR FRANCIS BOND HEAD, BART., K.C.H.,

ETC., ETC., ETC.,GEORGE HEAD.

29th June, 1837.

ADVERTISEMENT TO THE READER.

A HOME TOUR CONTINUED

VARIOUS PARTS OF THE UNITED

KINGDOM.

CHAPTER I.

ISLE OF MAN.

George Head, A Home Tour through various parts of the United Kingdom (London: John Murray, 1837) Conversion to HTML and placename mark-up by Humphrey Southall, 2012.